This summer marks the fourth time I have gone to the Kikai Institute for Coral Reef Sciences. Kikaijima is a small island located in southern Japan, which is rimmed with coral reefs. I became interested in this island because it is rapidly uplifting (about 2 m every 1000 years), so there are fossil corals here that date to periods during the last glacial cycle when there are few constraints on sea level position. This will be something I will discuss another time.

This year, I was serving as a mentor for the Kikai College science summer camp, which is held in the mid-summer period for children between the ages of 8 and 18. I was a mentor for the advanced course this year, where high school aged children formulate their own mini research project. This year, there were four general themes – Holocene coral growth rates, the health of coral reefs, the water resources on Kikaijima island, and microplastics in the ocean.

I was put in charge of the group focused on microplastics. Obviously, this is not a specialty of mine, but it was pretty straightforward to pick up the analysis methods. Microplastic is defined as plastic pieces that are less than 0.5 cm in diameter. One important thing is that plastic generally floats in the water – it will not collect at the bottom of the water where there is a lot of movement, such as along the coast.

The students had already decided on their projects before I got there, so the main task was to provide focus on collecting the data and hopefully providing a basis for their oral presentation that they had to do at the end of the 7 day program. There were three students in our group. One was investigating if microplastic can be found in the skeletons of the corals. The analysis she performed (basically dissolving the coral in a weak acid) did find something that might have been a microplastic particle. Another student was investigating if corals would eat microplastics. When she tried to feed the coral plastic, the coral actively pushed the plastic away. She was able to feed it plastic only if it was embedded in some bait. The third student was investigating if there was microplastic accumulating in the beaches of the island. I will describe this experiment below.

If you go to a coastal area anywhere in the world, you are bound to find plastic that has floated there on the ocean. Kikaijima is no exception. With a population of just 6000 people, they are not responsible for the large amount of plastic garbage that collects there. As shown in the first photo, it can be in the water in pretty high accumulations if the water flow conditions are right. The first photo was taken inside of a deep harbour where there is no current to circulate the water out.

The easiest way to find out where the plastic garbage is coming from is to find containers that still have labels on them. At every beach, we tried to find these containers and survey them. Because of the way the ocean current flows in this region, you would expect most of the plastic garbage to come from areas south of Kikaijima. You would actually not expect to find a lot of plastic from Japanese sources, as a result. The above picture shows bottles that come from China and Indonesia. In our surveys, we found that the majority of plastic comes from Taiwan and China, with only a few pieces from local sources and other countries, which included Philippines, Vietnam and even South Korea in one case. The above picture shows the only thing we found from Indonesia.

To investigate the microplastics in the beach, we collected samples of sand just above the most recent high tide level. I was kind of guessing that this might be a good place to sample. It turned out to be fortunate – the plastic floats! On beaches where there was no sand above the high tide level, there was almost no microplastics to be found. The microplastic concentrations will be minimal in places along the beach that are below the high tide level.

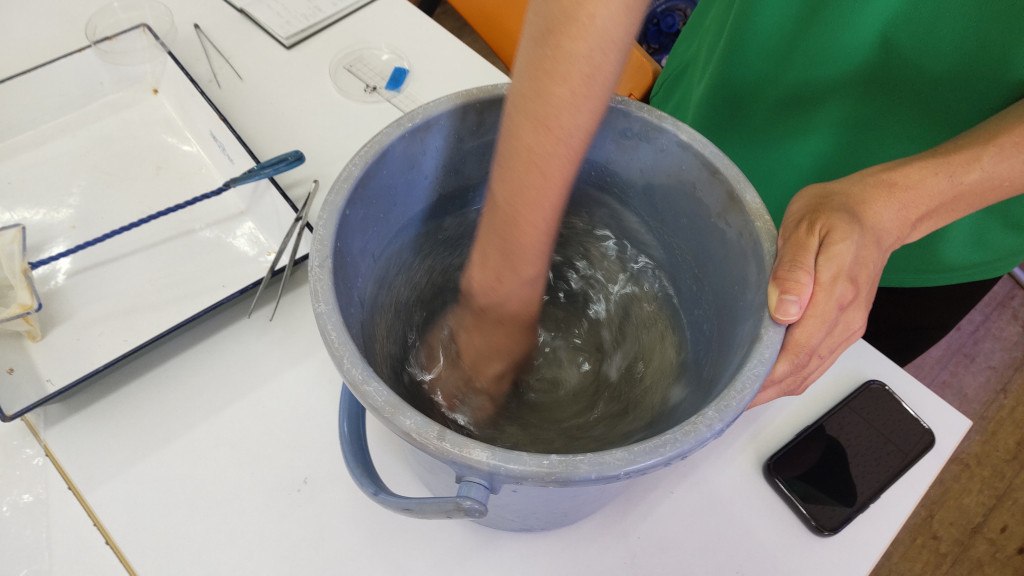

It is pretty straightforward to do the analysis for the microplastics. Since plastic floats, you put the sand in a bucket full of water, and swirl it around to release the plastic. You then skim the plastic off the top of the water with a net and put it in a tray. You then pick the microplastics out with tweezers. The complication with this analysis is that the sand is also full of pumices stones from a volcanic eruption that happened in 2021. Sometimes it can be difficult to distinguish between microplastic and pumice!

At the end of the analysis, it became clear that the main factor for the concentration of microplastics in the beach sand was the proximity to visible plastic garbage accumulation. The most microplastics were found in the sand near the garbage covered beach that is in the picture above. In clean beaches, there were sometimes no microplastics found, which is encouraging for the efforts to collect garbage on a regular basis. The student’s original hypothesis was that the microplastic concentrations might depend on which side of the island you are on. This is because the current is flowing northwards and is strongest west of the island. It probably would be difficult to find such a relationship, at least with the sampling method we used.

Anyways, those were the activities I did this summer in Kikaijima. I got to learn a bit about microplastics, and the difficulty in analyzing for them in the environment. The students got a chance to experience a full science project with a bunch of great scientists, and I think they had a lot of fun. I know I did!

You must be logged in to post a comment.